The Founding of the University

By Dr. Gerald R. Sherratt

The cornerstone of Old Main was laid on

March 14, 1897, by Principal Milton Bennion.

In the annals of American higher education, there is perhaps a no more dramatic founding of a school than that accorded Southern Utah University, nor a more striking example of the extent of the commitment of Utah’s early pioneers to the cause of education.

At the instigation of the Mormon colonizer, Brigham Young, Cedar City had been originally settled as a place for the manufacture of iron, the nearby hills containing abundant iron ore. Yet for all the fond hopes of Brigham Young, the “Iron Mission” failed for lack of fuel and water power and the need for more manpower. As a result, the people of the frontier community turned to other livelihoods, the majority becoming farmers, cattlemen and sheepmen.

By 1897, the year of SUU’s founding, Cedar City had emerged as a thriving – yet far from prosperous – rural community of nearly 1,500 people. Primarily of English and Scottish descent, the citizens of Cedar City were a hardy lot who had spent their lives wrestling with nature for the sheer sustenance and bare necessities of life. Isolated from the more populous centers of the West, they had learned how to nurse and care for themselves through injuries, illness, and accidents without professional help or much in the way of medicine. Demonstrating an uncommon degree of self-reliance and putting their faith in Divine Providence, they had built a community with the stark essentials – but few of the amenities – of life.

Old Main Building Committee

When in the spring of 1897 the people of Cedar City learned that the Utah Legislature had authorized a branch of the state’s teacher training school to be located in southern Utah, it was welcome news indeed, though few of the town’s citizens believed it actually possible for Cedar City to be selected as the school’s site. After all, Cedar City and Iron County didn’t really have much political clout. In terms of population, Beaver County to the north and Washington County to the south were both larger, Washington nearly half-again as big. Then, too, many people thought Cedar City was destined to be a manufacturing town and there were predictions that the city’s atmosphere would undoubtedly be smoky and unhealthy. Utah’s Dixie, on the other hand, had a unique climate which was especially nice during the winter months, and Beaver had an old fort which could easily have been converted to house the Normal School, as teacher training institutions were then known.

The bill enacted by the Legislature established a committee composed of three distinguished educators to make the final selection of the town to host the school and added the condition that the community so selected would have to vest the state with title to suitable grounds and buildings to house the school.

The selection committee was composed of the three most distinguished educators of the 1890s: Dr. Karl G. Maeser, Dr. John R. Park, and Dr. James E. Talmadge.

Immediately upon the Legislative approval of the bill, each of the communities of southern Utah began appointing committees and making necessary plans to influence the decision of the three men.

Cedar City set its machinery in motion at a mass meeting on March 21, 1897. Lehi W. Jones was appointed chairman of the committee, which also included John S. Woodbury and Edward J. Palmer, who were to serve as secretary and treasurer, respectively. This permanent committee served during the entire founding period, calling mass meetings as often as needed to discuss various plans and appoint sub-committees.

John Parry, Utah State Representative,

helped pass bill which authorized the

normal school branch in southern Utah.

John Parry, Cedar City’s representative to the Utah Legislature, had been instrumental in the passage of the bill authorizing the normal school branch, and he and Mayhew H. Dalley were asked to frame a petition to the commission setting forth the advantages of locating the school in Cedar City. The permanent committee set about drafting the community’s official proposal. Both documents were forwarded to Salt Lake City in early May, 1897.

Mayhew H. Dalley, cited the advantages

of locating the school in Cedar City.

The proposal drafted by Cedar City promised to deed to the state fifteen acres of land on the town’s outskirts upon which Cedar City agreed to erect a suitable building. The fifteen acres included a hill which had originally been set aside for a future Mormon temple and later was designated for possible expansion of the Parowan Stake Academy, the school system maintained by the Mormon Church. Academy Hill, as it was then known, consisted of five acres, the additional acres to be purchased by the contributions to be raised from Cedar City residents. Some lots were donated by the owners; others were purchased at a reduced price.

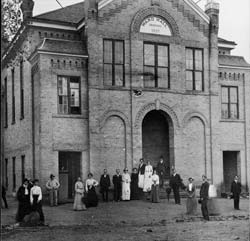

The Ward Hall served as the first home for Southern Utah University.

School was taught there starting in the fall of 1897.

The proposal also offered to deed some land in the heart of Cedar City on which a chapel and social hall were nearly completed. The plan was to use this building (known as the Ward Hall) for the school until the other building was constructed on Academy Hill, after which the Ward Hall and its land were to be returned to the LDS Church.

Cedar City was proposing to take on a massive task, and the community knew it. Nobody really knew how they would pay for the building. One plan was worked out between Cedar City and Parowan, both of which were competing for the Normal School. Under this plan, should the commission select either Cedar City or Parowan, the loosing city would contribute $2,400 in cash, materials or labor, to the winning community. All that was needed to make the agreement official was for it to be signed. Unfortunately, several hours before the scheduled signing, the word arrived that Cedar City had been selected; and the Parowan citizen hurriedly returned home, the unsigned agreement with them.

There is much conjecture about why Cedar City was selected for the location of the school. Members of the commission publicly said it was because of its central location and its excellent educational record but, privately, the determining factor seems to have been that alone of all the towns competing for the school, Cedar City was the only one without a saloon or pool hall.

The community was notified in late May of the commission’s action and for the next three months, it labored to complete the Ward Hall and make it ready for the first school year. In September, 1897, the school opened its doors for the first time.

School had been in session for only two months, however, when the town was thrown into its greatest crisis. The teachers’ payrolls had been submitted to the state for payment in late December, but the Attorney General refused to pay them since he ruled that Cedar City’s use of the Ward Hall did not comply with the provision of the law which required that the school have its own building on land deeded to the state for that purpose. Furthermore, the Attorney General stated that if a building was not erected by the following September, the school would be lost.

Henry Leigh, along with Lehi W. Jones and David Bulloch,

mortgaged their homes to guarantee teachers’ pay.

The immediate task, getting the teachers paid, was resolved by a loan from the Zions Savings Bank in Salt Lake secured by three Cedar City men (Henry Leigh, Lehi W. Jones, and David Bulloch) who mortgaged their homes to guarantee payment. The other task – getting the building erected on Academy Hill – was much more difficult.

Consider what needed to be done: the building would cost about $35,000, a sum which was only slightly less than the town’s total business volume for an entire year. If every family were assessed an equal share, it would have cost each family about $100. That doesn’t sound like much, but in terms of 2010 dollars it would be nearly $2,600. Further, winter had already set in and the town’s building materials were nonexistent because of the construction of the Ward Hall.

To the everlasting credit of the people of Cedar City, they set out to do the impossible. Nobody, they argued, was going to take their school away from them, not even if it meant bucking the mountain snows to get the lumber to construct the new building, which, of course, it did.

A five-man building committee consisting of Thomas Jed Jones, John Parry, Francis Webster, Thomas S. Bladen, and William Dover was appointed to whom the town pledged all its public and private resources; the committee being forced to dip into both generously. On January 5, 1898, a group of men, the first of a long line of townsmen to face the bitter winter weather of the mountains, left Cedar City. Their task was to cut logs necessary to supply the wood for the new building.

L to R: Thomas Jed Jones, received resource pledges. John Parry, on the building committee.

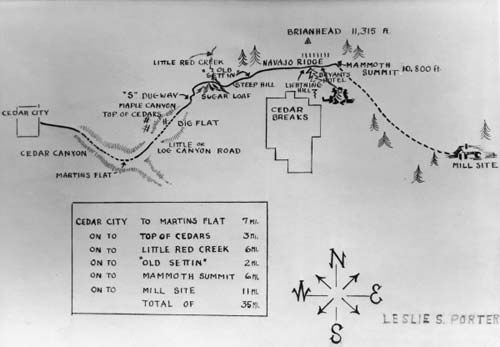

The first group of men who braved those mountain drifts proved genuine heroes. They waded through snow that often was shoulder deep, pushing and tramping their way up the mountains, sleeping in the holes scraped out of the snow and covered with mattresses of hay. They made their way over Lightning Hill, and then out across the plains known as “The Mammoth” and on past Cedar Breaks. It took them four days just to reach the sawmills, located near the present day ski resort, Brian Head. Once they got there they realized they had to go back to Cedar City again. The wagons they brought with them couldn’t carry logs through the heavy snows, and it was determined that sleighs were needed to do the task.

Founders’ route from Cedar City to the mill site where they obtained lumber to build Old Main.

The way back was just as arduous as the trip up. The snow had obliterated the trail the had originally blazed and the snow was even deeper. The wagons couldn’t make it and were abandoned at the clearing which remains known as “The Wagons” to this day. It was in this phase of their march that an old sorrel horse proved so valuable. Placed out at the vanguard of the party, the horse, strong and quite, would walk steadily into the drifts, pushing and straining against the snow, throwing himself into the drifts again and again until they gave way. Then he would pause for rest, sitting down on his haunches the way a dog does, heave a big sigh, then get up and start all over again. Years later, those who participated in that maiden trip into the mountains credited “Old Sorrel,” as they called him, with having been “the savior of the expedition.”

Back in Cedar City, the company worked three days – day and night – to make bob sleds by cutting wagons in half so that one end of the lumber dragged on the snow, which they found helped to keep the road packed.

The men were divided into groups. Some cut logs, some were sawyers, some planed logs into lumber, and others hauled the lumber from the mill. It took two and-a-half days to get a load of logs down from the mountain tops to Cedar City.

It was extremely cold in the mountains, temperatures dropping to as low as 40 below zero, and to protect their legs from the biting winds they tied rows of gunny sacks about their waists. Icicles hung from their mustaches. Word of the frigid conditions on top of the mountain was reported to the people of the town below, and steps were immediately taken to relieve the suffering. Loose-fitting underwear of heavy wool flannel was made to slip on over the men’s regular underclothing and heavy socks and mittens were knitted. The voluminous clothing made the outdoor work possible – but also more laborious.

Supplies of food for the workers and hay and grain for the animals were donated by the townspeople and sent to the lumbering site on the mountain each week. Every Cedar City home contributed supplies, including bread and pastries, flour, a variety of meats, butter, cheese, and fruits, as well as horses, harnesses, wagons, and other equipment needed in the lumbering operations. All the supplies were brought to the home of Mrs. Mary Corlett on Main Street and then dispatched to the men on the mountaintop.

Mary Corlett, gathered and dispatched supplies for the mountain expedition.

When heavy snows kept provisions from reaching the working men, they subsisted on a diet of dried peaches. From January through July they kept up their labors.

The bricks for the building, more than 250,000 of them, were made by a corps of men who remained in Cedar City, some of them putting in twelve to fourteen hours a day on the project. Actually, they had to make many more than 250,000 because spoilage was heavy due to sudden showers and frost.

Dedication of Old Main, October 28, 1898.

To purchase things which could not be made locally, cash was raised. Some people offered their stock in the Cedar City Co-op store, and fifty-nine stockholders in the Cooperative Cattle Company donated their stock which yielded $5,500. One man gave the siding off his barn. Richard Palmer donated some prized lumber he had been saving for his coffin, and Richard Bryant gave the lumber he had purchased to build a kitchen on his home for finish lumber for SUU’s first building. When September 1898 arrived, the building was almost completed. It had a large chapel for religious programs and assemblies, a library and reading room, a natural history museum, biological and physical laboratories, classrooms, and offices.

There has probably never been a more romantic founding of any school in America. The first building was literally torn from icy crags and molded by the hands of more than a hundred men and women. The community of Cedar City had met is greatest test, and Southern Utah University was given a heritage that few educational institutions possess.

The preserving of the University was achieved by people who would never attend it. Indeed, some of them had never had the opportunity of attending any school. They were hard, rough-spoken, courageous souls; people of the type without whom the frontiers of the West would never have been conquered.

They were also people of vision who knew the significant place colleges occupy in the American scheme of things and who were determined to secure the blessing of higher learning for their posterity and for their town.

Southern Utah University was founded by uncommon men and women. From its beginning the University has always known that its ability to meet the challenges of today and tomorrow rests in large measure with the success it has in sustaining the legacy of its founders, a legacy which calls for superior standards and for the shared belief that nothing the University can foresee, or sense, or conceive is beyond the collective will of its students, faculty, and administration. The lesson to be learned from its founders is that however difficult the task which the University faces, nothing is impossible.

The Founders Monument was dedicated in 1986.

The Founding of the University was first written by Gerald R. Sherratt, a 1951 alumnus of Southern Utah University who served as its 13th president from 1982 to 1997.