In collaboration with the Center for Teaching and Innovation

Josh Eyler is the director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and adjunct associate professor of humanities at Rice University. His eclectic research interests include the biological basis of learning, evidence-based pedagogy, and disability studies. He is the author of How Humans Learn: The Science and Stories behind Effective College Teaching

Reflection

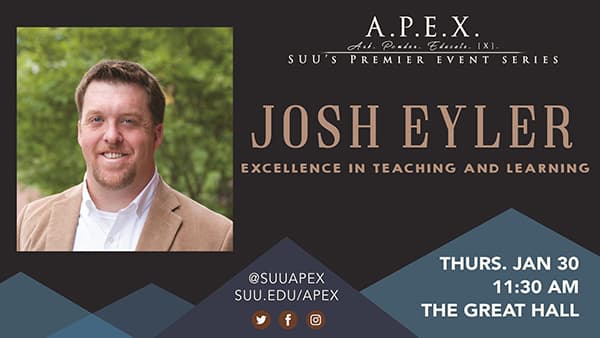

On January 30th, 2020, the featured APEX speaker was Dr. Josh Eyler, executive director of the Center for Teaching Excellence and adjunct associate professor of humanities at Rice University and the author of How Humans Learn: The Science and Stories behind Effective College Teaching. He was introduced to the stage by SUU’s Dr. Matt Weeg, Associate Professor of Biology and Director of SUU’s Center of Excellence for Teaching and Learning.

Dr. Eyler’s presentation revolved around the ideas and concepts from his book How Humans Learn, and how through scientific understanding of the psychology of human learning, educators can utilize this understanding to approach teaching at a post-secondary education level to give students the best education possible. Eyler talked about the importance of failure in the classroom and authenticity in both teaching and learning, and how educators can utilize some of the tips he mentioned from his book and not only help their students really understand the concepts being learned in the classroom, but also help the educators to be better teachers to their students and to be more transparent and clear in what they want their students to take away from the day’s material. In his presentation, Eyler encouraged making failure a normal and healthy part in the learning process as well as emphasizing feedback from students, lessening the value of the grading scale in students’ education, encouraging creativity and group discussions, and using emotion and storytelling in the classroom to engage and captivate students and to show them that their teachers don’t just care about what they’re learning or how well they’re understanding the material, but also about the students as individuals to best help them succeed both in school and in life.

- By Emily Sexton

Josh Eyler Podcast Transcript

[00:00:01] Hey, everyone, this is Lynn Vartan and you are listening to the A.P.E.X Hour on KSUU. Thunder 91.1. In this show, you get more personal time with the guests who visit Southern Utah University from all over. Learning more about their stories and opinions beyond their presentation on stage. We will also give you some new music to listen to and hope to turn you on to some new sounds and new genres. You can find us here every Thursday at 3:00 p.m. or on the web at suu.edu/apex. But for now, welcome to this week's show. Here on Thunder 91.1.

[00:00:47] OK. Well, welcome in, everyone. This is Lynn Vartan, curator of Apex Events. I am so happy to be here today. We are talking about teaching and learning. You know, every week is a different topic for our event series here at Southern Utah University and this week we're focusing on the science and psychology and all things about teachers, teaching and learning. My guest is Josh Eyler. Welcome into the studio, Josh.

[00:01:15] Thank you. Lynn. Great to be here.

[00:01:17] Well, it has been so fun to talk to you. And you have this great book which we're totally going to get into talking about. But the name of the book is How Humans Learn. But before we get into the nitty gritty about the book and all of your research, I'd love to just talk a little bit about who you are and your current position. You're doing some really exciting stuff at the university that you're at session. Tell us a little bit about what you do.

[00:01:39] Absolutely. Well, I currently work at the University of Mississippi, where I direct teaching and learning initiatives and work on a university wide critical thinking program. I'm also faculty in the Department of Writing and Rhetoric. So a little bit of everything, but that continues work that I've done for the last 10 or so years at other universities with these same kinds of teaching and learning programs. So I'm really enjoying it. We just moved a couple of months ago and love my new colleagues and it's a great place to address some of our biggest challenges that we have in teaching and learning with some great colleagues.

[00:02:14] That's so cool. And previously you were at Rice. Is that right?

[00:02:18] Yeah.

[00:02:18] Yeah, for a long time. And you did similar things there?

[00:02:21] I did. Yes. I directed the teaching center there. And we worked on, I just had an amazing group of folks who were working together to improve teaching on campus and the learning experience for students.

[00:02:33] And at the moment, right now, you're working on a large initiative. And can you talk a little bit about the scope of that?

[00:02:41] Right, sure. Yes. Well, because of the region that our universities and we're required every 10 years to put together a major quality enhancement program for the university and we have chosen critical thinking in the gen ed program. So our goal is to enhance the critical thinking skills that students develop in the first and second years of their time at college. And so we you know, we're addressing a number of ways. I work with cohorts of faculty to to revise their courses, to build more opportunities in there for students to develop those skills, change assignments, activities, things like that, do a lot of workshops across the university to give a kind of a range of perspectives on the research and strategies that you might use. And we're working with departments and programs all across the universe.

[00:03:33] One of the things that came up at lunch was this discussion of what exactly is critical thinking. And I found that to be a really interesting because, you know, I use those words all the time yet critical thinking skills, you know. But now, because of our conversation, I'm thinking, well, you know, I may have a different definition of that. And was it sure that one of the things you found was that everybody defines critical thinking a little bit differently and how did you solve that?

[00:04:00] Oh, certainly. I think. I think if you polled people in higher education across the country, I think every you'd come up with as many different definitions of critical thinking as you would people.

[00:04:11] Right.

[00:04:12] So and that's, that's natural. We all come from different disciplines, different backgrounds. The traditions of our universities are different. So I understand why. But if as a university you want to make improvements in this area, you have to come up with a definition that works for you that you can use to develop programs, that you can measure progress on the goals that you set. So we as a team, we were much more drawn to the research that suggests that critical thinking is a discipline specific skill. There is other research that says it could be generalizable regardless of context. But we think that ought to be a good critical thinker, in biology, for example, you have to know information and theories in biology before you can build those skills.

[00:04:59] I love that.

[00:05:00] That's kind of the core philosophy of our program. And we're just working with faculty departments, programs across the university to see what what the needs are and what is the best approach for a particular program or a particular faculty member for doing that.

[00:05:15] And that's not to say that critical thinking can't occur across disciplines. You don't take those skills with you. But as a core kind of starting point, you have to have some established knowledge in the field.

[00:05:27] Right. And particularly because we're looking at the gen ed program the first two years, there has to be a way for us to say to show progress from the beginning of freshman year to the end of the sophomore year. If we were doing a four year initiative, it would be easier to say, OK, during your four years at the university, we hope you develop these generalized critical thinking skills. But in the first two years, really, if you want to show improvement, you have to look at the course level and the program level.

[00:05:59] Right. Did you find that in, one of the things that we're always talking about is communication across campus. Even if you're at a new school now trying to gather information from everybody from all over the place. Did you find challenges in communicating across campus? Do you have any tips for those of us in academia who want to increase our level of communication across campus?

[00:06:25] Well, yes, I do. I think that one thing I learned very early on as I moved into working in this area is that it was really, it was really important for me to learn the vocabulary, the methods and the habits of mind of people in a wide variety of disciplines.

[00:06:46] Oh, wow.

[00:06:46] If we're going to have a conversation about critical thinking, but there are others like what's interdisciplinary mean?

[00:06:53] That's a good point. Yeah.

[00:06:55] So if we really want to do cross campus work, we have to have opportunities to bring people to the table to develop a common language and common toolset for dealing with that. And so that's really what I've been trying to do. It's about working with folks from across disciplines. So what when you think of critical thinking in your courses, what are you trying to achieve? How does it map on to, you know, these these goals that we've set as a university? And there then. I mean, it wasn't to make very clear that in no way was this program suggesting that people hadn't been teaching critical thinking.

[00:07:31] Right. Right. Of course.

[00:07:32] That what we were interested in is a very specific version of it and ways to actually show that students were making progress on these six goals. So individualized conversations were the way that we could do that and then come together as a group.

[00:07:46] Yeah, cool. So many questions for you. But one of the sort of obvious ones is that your, your background, like you didn't wake up one day as a seventh grader and say "Oh, my gosh, I'm going to study the science of teaching and learning." You have a very different background, I think in the classics. I'd love to hear a little bit more about, you know, how you transitioned and what that transition was like and how it feels.

[00:08:11] Yeah, definitely. You're absolutely right. I've been in the humanities my whole career, my Ph.D in Medieval Studies. And so my first job, I was a tenure track faculty member, an English department at a school called Columbus State University in Georgia. And, you know, taught, the full range of courses, Beowulf, Chaucer, the whole works.

[00:08:36] That's awesome.

[00:08:36] And what really shifted for me was that I was able to see at that, that midsize university in a small Georgia town, the effect the great teaching had on individual students' lives. It was the, the power of education was on full display there. And that really, really had an impact on me. And what I wanted to do was to find a way that I could help make that possible for more students than just the ones that I saw every day in the classroom or even beyond my department's impact. I wanted to see if I could be a part of the conversation at a national level so that we could get traction on helping every student have the kind of experience that matters for their lives, not just within the context of an individual course or semester.

[00:09:31] And have you ever looked back? I mean, are there those times where you just go like, "Wow, this is just such a big thing to tackle?" I mean, it seems I mean, overwhelming, perhaps.

[00:09:43] Well, if you had to take a little bit at a time and focus on a piece of it, I think. It was, in some ways it was a hard decision because I gave up tenure to move into the school.

[00:09:54] Oh, really? Oh.

[00:09:54] And so that I recognize and not everyone can do that for a variety of reasons. And it was, it was hard. And so there is some you know, there's lots that go into that. But for the most part, moving, making that move allowed me to work at a different level at the university that I wasn't able to to work at before. And that gives me that kind of perspective on, I think, on the work of the university, but also teaching and learning in higher ed writ large. That helps me be able to say, "OK, we're not going to change everything all at once." But just like in one person's classroom, incremental changes over time matter quite a lot.

[00:10:40] Yeah, absolutely. And as you've worked with teaching centers and developing these things, I mean. Do you, do you find that everybody is really excited about this kind of thing, or do you find sometimes that people are like, "Don't tell me how to teach, I don't, I don't want to change anything." I mean, is that, what sort of is more often the threat and not just at your institution, but maybe in your experience at large.

[00:11:05] Definitely. The reactions are all across the board. But and certainly I've seen resistance, although not, not very often. I think the common demoninator, what I've seen most often everywhere is that most people went in to this profession to help students.

[00:11:24] Right.

[00:11:25] So regardless of what reaction I'm seeing about a particular program, once you actually engage in conversations about, well, what do you want? What do you want your students to achieve? What what is it that you want to be teaching them? That changes the dynamic. And so I definitely understand the skepticism of, of any kind of impulse where it seems like someone's coming from a top down approach and say, "you must teach this way." And so try never to frame it as that. You know, there's so many different ways to teach really effectively. What I want to help people find is the way that works best for them.

[00:12:05] All right. Great. I love that individual approach. Well, we are speaking with Josh Eyler. The book is called How Humans Learn. And it's time for a song. So let's see, what do I have for you today? The great bass player, Avishai Cohen. I've played it quite a bit. I've played sometimes here. But I have a song here that I really like of his. It's called "One for Mark." And you're listening to KSUU Thunder 91.1.

[00:17:04] Okay. Well, welcome back, everyone. So this is Lynn Vartan. This is the A.P.E.X Hour, KSUU Thunder 91.1. That song was one for Mark by Avishai Cohen. And just a reminder, if you're interested in the music that I play on the A.P.E.X Hour, there's a public playlist on on Spotify. But there's the link to it on our web page, which is suu.edu/apex. You can check out the playlist for all the songs that have been played on the A.P.E.X Hour. We are in the studio with Josh Eyler. Welcome back, Josh.

[00:17:40] Thank you, Lynn.

[00:17:41] Josh is the author of How Humans Learn, and today we were talking about teaching and learning, and I'd love to get into some of the concepts that are in your book. There are sort of five main, you know, points, not so much points, but concepts that you build up and around. And one of them that I know is a favorite for yours is emotion. And it's not in that chapter, but in the introduction, you say, "Hey, listen up, I need to tell you a story." It's something like on page two or something like that. Great little quote there. And in the emotion chapter, you talk about storytelling and the importance of storytelling as a teaching device. And I just would love to kind of talk about that a little bit and hear some more of your thoughts.

[00:18:24] Sure. Definitely. Well, yes, storytelling. First of all, it's one of the absolute oldest teaching strategies. I mean, the way people learned for a very long time was through the stories that the people in their community told them. And so this goes back a very, very long way. But, you know, storytelling as a teaching strategy has the ability to tie in our social natures as human beings. The emotional component, they're authentic. And so there's, there's lots of ways of storytelling, I think, really matters and helps in the classroom. There's been some really interesting research to show that people have developed more empathy through stories both telling and listening. One of the things we know about our brains is that they will frequently try to fit information into a story that placing bits of information into the context of a story helps us to remember more and helps us to draw that back out. So what we remember is the story and then that ties to the information. And so it's true that in every discipline there are ways that we can frame the material that we're teaching through stories that are somehow connected to that. Now, one good example of a mentor of mine at Rice named Kathy Matthews, she's a biochemist beloved by students and colleagues alike. And she tells, she teaches Intro to Biochemistry, that kind of thing. And she will typically tell the stories behind the discoveries that were made. And so when she teaches about, you know, DNA and the Nobel for that, she'll talk about Watson and Crick and and, you know, all the mistakes they made along the way. You know, some of the scandals that happened as a part of that. So she frames what could be, in some cases, pretty dry genetic background through the lens of these really interesting stories about the people who made the discoveries and who contributed along the way. I think there are many examples that we can use for that or that tie into that, because our students really do respond well to stories.

[00:20:40] So when you're working on, you know, a class of yours or helping a colleague, I mean do you sort of look through the content and try to say like, you know, talk through those, like, how do you help someone make a class better in that way or incorporate stories or help? What's that process like?

[00:20:59] Right. Sure. Well, can look a couple of different ways. Sometimes people will come and say, you know, I really want to try something new and we can talk through it that way and to think about, okay, well, this is a really interesting topic. Why did you select it? What's interesting to you about it and kind of go from there. Because sometimes the stories can be about you and as the instructor and your, the stage as you went through and the discipline and that sort of thing, or it can be it can be other kinds of stories as well. So sometimes it's that sometimes folks will ask me to come observe their class and there I get, I get in real time what's happening and how the material is being framed. And that can help us brainstorm possible uses of storytelling that might that might shift the way the material is delivered a little bit more. So it can come from a number of different angles.

[00:21:55] Cool. And one of the other topics in the book is, is failure. You know, and I'd love to get into a little bit about, you know, any, any best practices and maybe a bit about the importance of it, but best practices to incorporate more failure into your classroom. Which of course sounds so counter-intuitive at first, but we do need that.

[00:22:17] Yes, definitely. I think we could call it error. We could call it mistake, failure. It's all a piece of the same puzzle. And what we know is that people learn best when they're given an opportunity to try something out, make a mistake and get feedback on that and begin the cycle all over again. And so that's the importance of failure. Our brains are designed to detect those errors when they're made and to draw resources to that. And so this is really how we're built. And so if we design educational experiences that somehow arrest that cycle before it can play out, we haven't we haven't allowed students to really learn in a way that they're ultimately be successful. So that's kind of the importance of it. How do we do it as a whole other volume.

[00:23:07] Yeah.

[00:23:09] Because we're, you know, our educational systems are not set up in this way. We frequently just give students really high stakes tests, one chance. Not a lot of room to learn from the feedback that we're giving them for that particular assignment. So here are some things that I've learned that I think people are experimenting with and having really good success with. One is very simple, although it does require planning, to break down the course grade into smaller increments. And so rather than four exams each worth, 25 percent of the grade somehow implement other small, low stakes assignments that students can practice the skills that you need them to develop in a way where you're giving them feedback, but not necessarily grades or if you're giving them a grade, it's for a much smaller percentage, which has the effect of helping them learn from the assignment, but also take some of the pressure off of the those exams as well. Because if you know, if, if students are in a circumstance, a situation where they know they're taking an exam that's worth 25 percent of their grade, there is no absolutely no incentive for them to take an intellectual risk or try something out they might not get right.

[00:24:27] Right.

[00:24:28] So that's, that's a small thing. Things that I love that people are trying, two things. One, group testing, where students will take an exam as an individual. And then the next day or later in the period, they'll take the same exam as a as a group and try to defend their answers and convince each other of who's right and how did they get this answer. And then the fact that, I've seen a range of approaches, some faculty average those two grades, some weight them slightly differently. The point, though, is that drawing on a lot of what we know about how learning happens to really help students succeed in that particular arena. So that means for failure with connection to failure, if you make a mistake as an individual, A, it doesn't count as heavily against you and B, you actually get to learn from the group that you're with why you may have gotten it wrong.

[00:25:23] Right.

[00:25:25] So that's one thing. Another thing that I really love, that people are experimenting with multiple choice tests, that where the focus is not entirely on getting the correct answer. And so the ones that I've seen, the models that I love and hold up often are they'll start with. OK. What's the correct answer? But the next question is choose another answer and explain why it's wrong.

[00:25:48] Oh, I love that.

[00:25:49] And they have another step that says now choose another answer and show what the question would have had to look like for that to be the right answer.

[00:25:57] Oh, that's great.

[00:25:57] So there are different ways they play with it. But the point is, it's not all about getting it right.

[00:26:02] Yeah. Oh, my gosh. Those are real gems. Thank you.

[00:26:05] Those are people are really having good luck with those.

[00:26:09] Oh, that's great. Well, I'd love to move into social, the social aspect of it.

[00:26:14] Sure.

[00:26:14] Sociability or sociality. And and talk about some best practices. I know that, you know, discussion is one of the strongest, you know, elements or pedagogical tools that we can use. I'm always curious about it, because I think for me personally as a student, but not so much as a teacher, but as a student am I tended to like learning on my own and like figuring things out myself. And so I wonder sometimes I would have been the kind of student who wasn't as in favor of like discussion type things. But I was just curious because I know discussion so important. So maybe talk to us a little bit about that, a little bit about some other ways to increase that social connection in learning.

[00:26:59] Sure. Well, the I mean, it is true that discussion based teaching has the ability to be one of our most effective social pedagogies. But there are certain things that we need to do to make that happen.

[00:27:13] Right.

[00:27:14] So I sympathize with those students who are sometimes in discussion environments where they're thinking, you know, this is great, but what am I learning? Right. You know, we're talking to each other, but am I learning anything?

[00:27:26] Right.

[00:27:27] That's really the tricky part.

[00:27:28] Right.

[00:27:29] And so a couple of things. We had to pay close attention to our goals for the discussion. Where do we want students to be at the end of the class session? What, what direction should they have been headed in and what kind of knowledge do we want them to have generated together? We had to be very transparent very early in the semester about what the purpose of discussion is. And that's a step that I myself am guilty of skipping over, thinking, for example. That's just intuitive why we're having a discussion. But the research suggests that we need to be really transparent with students about why we feel discussion is the best strategy for helping them to learn. And then the third thing is being very intentional and paying close attention to the kinds of questions that we're asking. In other words, a lot of open ended questions rather than closed ended questions because they kind of shut down conversations. But also not being afraid to ask questions. And I will acknowledge this is harder, especially early in a teaching career, but not being afraid to ask questions that we don't know the answer to.

[00:28:43] Right.

[00:28:44] Because that lets everyone in on the project of oh, hey. Well, this is let's take a stab at it. Let's let's try and figure out an approach and bringing a lot of people's thoughts to bear on a particular topic when there might not just be one set answer and there may be several, several ways of addressing a particular problem.

[00:29:05] Yeah, I think one of the things that I see a mistake made is people, discussions tend to just end up being, "Well, what do you think about this and what do you think about this and what do you think about this? And it's a lot of unfounded information. But I think that those setting goals, you know, of what you want to happen and what you want them to have learned, you know. What are your objectives, I think will make a big difference in that.

[00:29:32] Exactly. And so two things about that. One is you're absolutely right. There is a limit to how open the questions can be and still have learning taking place. It's OK to sprinkle in every now and then, what do you think about that? But, you know, this gets back to your earlier comment. Too many of them. And the class is really just a litany of people's opinions about things rather than learning. The other thing I think that's important is that even if students haven't, haven't yet develop the skills to completely answer a major question in the discipline, that doesn't mean that they won't learn something in attempting to answer that question. And so as a part of discussion, we can, we can throw out a big question, right? Scholars disagree about this. Some think this and some think this. What do you think and how and why would you approach it that way? And you know that because they don't Ph.D's in our discipline that they probably won't get as far as, you know, a scholar might, but going through that process and attempting, there's a lot of learning that happens.

[00:30:42] Right, right.

[00:30:42] So we need to have, give them some freedom to do that kind of work.

[00:30:48] That's, that's great. Think that's so helpful for that. I'd love to zero in a bit more on the transparency component. And I'm, I'm a big fan of that. You know, I feel if you're if you're really being transparent at every step of the way of why, that gets to a bit of the authenticity component in your book as well. Well, you know, why are you doing this? What are the applications for it? That kind of thing. Right. What advice or best practices or whatever can you think of for people who want to sort of check on their transparency and because what happens, I mean, I'm sure I'm guilty of it too, you get so in your, in your sort of process that you take for granted, perhaps that they understand why they're doing this particular thing. It may seem obvious to you. So if somebody wants to sort of examine their transparency or any best practices regarding transparency, I'd love to hear about that.

[00:31:47] Definitely. Well, I think one basic premise here is that it's hard to be too transparent. Right. You know, and I mean, so if you feel as if it would benefit students by talking about why you're doing something or why you've structured it and examined the. They designed these questions, and certainly Ivan and I know many also who do this will bring in research about a particular teaching strategy and show students and say, "Here's why I'm doing this." And we'll even sometimes have a discussion about, about the data that I'm showing them. But it's hard to be too transparent. So one best practice, I would say, is you can always ere on the side of being more transparent than less.

[00:32:30] Right.

[00:32:30] The other key and I think this is a bigger one and this connects to a lot of teaching dilemmas, getting frequent student feedback will help you in almost every aspect of teaching. In fact, I sometimes joked if someone cornered me and said, "what's the one thing I can do right away to be a more effective teacher?" I always say get student feedback as frequently as possible. With transparency in particular, it's possible to say, to give them a short minute paper at the end of class, or model points on some sort of, some sort of tool that asks them, "Do you know why we did what we did today? Do you know why we did it this way?" And the answers will help you see whether or not you need to be more transparent. Now, in this case, when I see student feedback, I genuinely mean feedback that we get that's meant to improve our teaching and their learning. I'm not talking here about the end of semester.

[00:33:27] I was just, you totally took the next question, because that's where everybody goes, right? Because the end of the semester evaluations. I know we've struggled with them here first finding the right format and finding the right thing and then that, the way students interact on those and the questions, even with the best intentions and trying to formulate the questions, the best possible way, the feedback is not what I think what you're talking about, which sounds much, much better right now.

[00:33:57] This is you know, some people I know will get that feedback every day. Some people once a week, some people once, you know, at midterms, right? But the key is that is our best tool. And seeing if the, in creative writing, they talk about that a lot, does the intent marry the effect? Does our intention lead to the effect that we're hoping it will and that feedback really helps with that.

[00:34:22] Yeah. So some of those questions like do you did you understand why we were doing this particular activity or why it was presented in this way or why this exam was, those, I mean, I hadn't really thought of doing those kinds of assignments or getting that kind of feedback.

[00:34:38] And that's particular to the transparency issue. Most, most folks use a version of a minute paper, which was a tool developed a long time ago. And it really has three questions on it. What worked well, what didn't? And, you know, what should I, what could we do more of it? Or they'll use something that folks call a model point, which is really students just write down what are they still confused about.

[00:35:05] That's great.

[00:35:05] And now you get that's, that you come in the next day or so and go, "it seems like I could have been clearer about X topic and talked about for a few minutes and then you can go on to the work of the that day's class".

[00:35:19] That's so cool. Thank you. All right. It's time for some more music. So this is an artist called Nathalie Joachim, J-O-A-C-H-I-M. And this is a prelude. It's "Suite: pou Dantan." And you're listening to KSUU Thunder 91.1.

[00:38:54] OK. Well, welcome back. I do want to tell you a little bit more of that song. This is Lynn Vartan. You're listening KSUU Thunder 91.1. This is the A.P.E.X Hour. That song that was the first movement of a suite, now. So it was the prelude of "Suite: pou Dantan," the artist was Nathalie Joachim. But also, I wanted to mention that the Spektral quartet, string quartet, Spektral being S-P-E-K-T-R-A-L, Spektral Quartet is also on that album and on that track. And it's a really interesting sound as you probably heard. So. Anyway, back to talking about teaching and learning. Welcome back, Josh Eyler. The book is called How Humans Learn. And I just so enjoyed it. And you can definitely get it anywhere where you get your books are either in each version or a paperback or whatnot. So I would love to, we've been talking about all the great, you know, some of the great tactics, best practices, on some of the things that we could do. And and, you know, of course, in our education system, there are some things that have gotten in the way of some of those things we've talked about, you know, that the high stakes grading and how that it's affected our students. I'd love to know a little bit like if you had your dream education system, if you were going to rebuild things from the ground up in America, what would that look like? Like what kinds of things would you, let's say there was no, you didn't have to talk to anybody. You just could build it on your own, you know, as it were. What are some what are some of the things that you would really love to see in there?

[00:40:30] Oh, to have that power. This is one of my favorite questions I've ever been asked. I like it.

[00:40:36] All right.

[00:40:37] So the first thing that I want to say is that in my dream world, states give as much funding to schools as they need and we pay teachers like the professionals that they are.

[00:40:49] Yes, amen, brother!

[00:40:51] That I think would make a lot of these other things possible. Okay. So then in elementary school, I think the one thing that the teachers I talked to were pretty clear on and the research is also clear and the fact that there is agreement there I think is really telling. And that would be that we should focus, especially in the earlier grades, much more on helping children develop self-confidence, self-efficacy, helping them find what they really are interested in and fascinated by. And a lot of play like two or three recesses a day, not just one. There is so much work out there that shows the connections between giving little kids the freedom to play. And that frees up some time then for learning as well. So the younger grades need to be developing the kinds of personal skills that will let them be successful once they get to the age where, you know, developing content knowledge and skills becomes more important. So I think that's really important. You could had a lot of math anxiety and test anxiety off at the past if you spent more time at those ages helping them cultivate confidence.

[00:42:06] Do you think that's always been a need or is that something that's more of a need now than ever? Perhaps because things are different at the home and you know, people are so spread with all they're responsible. Is it more now, less now, or is it just always been a need and always should be there in the classroom?

[00:42:24] I think it's always been a need. I think people haven't changed very much. I think that they're, I think that our educational systems have changed. And the amount of time focused on content and test prep and all those things has increased.

[00:42:41] Right. Right.

[00:42:41] And so in that way, there might be a little bit more need now than there used to be. But in general, these are things that the children need overall. So elementary school, I think that would be really appropriate. Middle school. I think we also need to help students. Content becomes really important, but so does also the arts and physical education, really making sure that the children understand that the world is more than, just, just content knowledge, that there's a lot more to it. At those ages middle school, it's also really important, I know some schools are moving in this direction, helping those students develop social emotional intelligence.

[00:43:24] Yeah.

[00:43:25] Helping them to understand a lot of what makes the world work, right? And really thinking about the social dynamics of of the world and everything that comes into play.

[00:43:39] And same question with that. I agree 100 percent. Is that, is that need something that you see more now or is the world so accepting, is the pace so accelerated that students maybe need that social knowledge earlier, is it, is it different than it was in the past? Do you think?

[00:43:59] I think, I don't know about at the middle school age. I, maybe more in high school. I do think, here are two things. One thing is that especially as they get older, social media becomes more, plays more of a role in their lives.

[00:44:17] Right.

[00:44:18] What we know from research on social media is that the images that people put forward on social media are carefully curated. Yes.

[00:44:26] And so as adults, it's easy to see that.

[00:44:31] Sometimes, not all the time, even we have trouble with that.

[00:44:34] That's true. It's easier when you're 16. You may not know that the perfect images that you're seeing are just are curated, and are very carefully selected. And we see a lot of work now showing that, you know, teenagers are judging themselves against images that, that may not entirely be true, right?

[00:44:55] Yes.

[00:44:55] So social emotional intelligence and the ability to kind of work through a world dominated by social media.

[00:45:03] That's so cool. What would a class like that be like?

[00:45:05] I don't know. I don't know. I think that we if we made more space over the course of a school day now, it would be possible to do that. Also possible to, I think, build it into the curriculum.

[00:45:19] Yeah.

[00:45:20] You know, I teach English. And so I can think of lots of ways that you could talk about the relevance of particular thing that you're learning about a piece of literature to their life.

[00:45:30] Absolutely. Yeah.

[00:45:31] So I think that's the key. I also think at middle school and high school, parents, we don't get off scot free. There has been certainly a trend over the last few decades to try and involve our children in as many different activities as possible. So we're culpable for increasing how frenetic their lives have been.

[00:45:57] Yes, right.

[00:45:58] And so, you know, looking really carefully at that as well.

[00:46:02] Well, as a parent yourself, I mean, that's it's such a tricky, I mean, how do you balance that?

[00:46:08] Sure. You want the best for them and you want to. You want to help them find what they want, what they really enjoy. Right. And I think that there's also was some kind of a pressing need, an invisible need that's out there. If we don't do enough right now, are we preparing them for what's to come?

[00:46:29] Right. Right.

[00:46:30] And so, you know, there's a give and take with that. And it has to be a, it's a fine balance right?Now, college...

[00:46:37] Yeah, let's hear it.

[00:46:40] I think lots of things. I think that there, that we should invest more time in helping students, especially early on, discover what they really are passionate about, what, before they pick a major, let's help them decide "What do I want my life to be like? And how does my career fit into the life that I want to lead? How can I marry those together in a college curriculum?" And the reason I say that is because students at that point have spent so much time in their lives preparing to get into college. There hasn't been a lot of attention paid to "What do I do now that I'm here?"

[00:47:17] Right. Right.

[00:47:18] Go to college absolutely knowing what they might want to do. But many do not. And so I think helping students see how it's an yet another stage on leading a meaningful life. I think it's important.

[00:47:31] Yeah.

[00:47:31] Another thing then, putting much less emphasis on grades.

[00:47:37] Yes.

[00:47:37] Much more attention on, on feedback and helping those students develop the skills that they will need to pursue whatever career they want to pursue. And finally, I think, you know, a lot of the some colleges are having really great luck with interdisciplinary studies or self crafted majors. I think there's a lot of opportunity there to explore. And certainly there needs to be guidance for those efforts. But let's say a student wants to be an animal behaviorist, right. In a traditional college, that would probably look like a student having a double major in biology and psychology.

[00:48:22] Right. Right.

[00:48:24] But there's a whole other possibility where we could, with guidance, help us student craft a major that were that would benefit him or her more than the double major.

[00:48:35] Right. Right.

[00:48:36] So that's, that's going to my pie in the sky view of education could be.

[00:48:42] I love it. That's it, the world according to Josh Eyler.

[00:48:46] Right?

[00:48:46] Perfect. Well, no, that's it's really cool to hear because. Yeah. I mean, we can spend a lot of time deciding what we're not doing and all that. And it's kind of fun to dream a bit and say like, well, what, what does it look like, you know? And that is sort of helpful in a way somehow.

[00:49:01] I agree. Definitely.

[00:49:03] Well, we have one last song to play, and then we'll come back for our favorite last question. But this last song that I have is called "River Rises." The group is called The Gaddabouts. And it's a whole bunch of people. It's Edie Brickell, the singer, Steve Gadd, the amazing drummer, Andy Fairweather. There's Andy Fariweather Low, there's just a whole bunch of different people on this song. It's kind of a big collaboration. Check it out.

[00:53:30] Hey cool, well, I'm gonna get us back in here because we just have a few minutes to, that's a good place to stop right there. That song was "River Rises" by the Gaddabouts. This really cool collection of a ton of great musicians just getting together to play an album. So anyway, I'm back in the studio with Josh Eyler for our last little break. Welcome back, Josh.

[00:53:55] Thank you.

[00:53:56] So I have a question that I love to ask every guest and I'm going to ask it to you. It's the question is like, what's turning you on this week? And it can be anything. It could be an album. It could be a TV show. It could be a movie. It could be a book. It could be some crazy food item. It could be anything but just an opportunity for audience to kind of get a little more insight to you. So, Josh Eyler, what's turning you on this week?

[00:54:20] Well, it is the final season of Schitt's Creek.

[00:54:24] Oh, yes. Best, the best.

[00:54:26] Yes. And my wife and I love that show. And so we're, we've been watching the episodes of the final season. So not only is it hilarious, which is, you know, it's just a great way to end the day. But I just love the premise of the show. You know, Daniel Levy has talked about, imagine a world where you have all these quirky characters, but everyone's free to be themselves and love whoever they want to love. And I just think that that's an amazing message that we need to have more of.

[00:54:54] 100 percent agree. Thank you. What a great one. Well, that's the end of our show for today. So we'll leave you with that wonderful thought. Thank you, Josh, so much for your time. Thank you for the invitation. And thank you all for listening. See ya.

[00:55:09] Thanks so much for listening to the A.P.E.X Hour here on KSUU Thunder 91.1. Come find us again next Thursday at 3 p.m. for more conversations with the visiting guests at Southern Utah University and new music to discover for your next playlist. And in the meantime, we would love to see you at our events on campus to find out more. Check out suu.edu/apex. Until next week, this is Lynn Vartan saying goodbye from the A.P.E.X Hour, here on Thunder 91.1.